Algebraic geometry¶

Let’s consider a geometric entity (e.g. line, square), whose properties can be described using a system of \(m\) polynomials:

We will call \(\mathcal{H}\) a hypothesis. Given a theorem concerning this geometric entity, the algebraic formulation is as follows:

where \(g\) is the conclusion of the theorem and \(h_1, \ldots h_m\) and \(g\) are polynomials in \(\mathrm{K}[x_1, \ldots, x_n, y_1, \ldots, y_n]\). It follows from the Gröbner bases theory that the above statement is true when \(g\) belongs to the ideal generated by \(\mathcal{H}\). To check this, i.e. to prove the theorem, it is sufficient to compute a Gröbner basis of \(\mathcal{H}\) with respect to any admissible monomial ordering and reduce \(g\) with respect to this basis. If the theorem is true then the remainder from the reduction will vanish. In this example, for the sake of simplicity, we assume that the geometric entity is non–degenerate, i.e. it does not collapse into a line or a point.

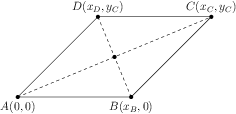

Let’s consider the following rhombus:

A rhombus in a fixed coordinate system.

This geometric entity consists of four points \(A\), \(B\), \(C\) and \(D\). To setup a fixed coordinate system, without loss of generality, we can assume that \(A = (0, 0)\), \(B = (x_B, 0)\), \(C = (x_C, y_C)\) and \(D = (x_D, y_D)\). This is possible by taking rotational invariance of the geometric entity. We will prove that the diagonals of this rhombus, i.e. \(AD\) and \(BC\) are mutually perpendicular. We have the following conditions describing \(ABCD\):

- Line \(AD\) is parallel to \(BC\), i.e. \(AD \parallel BC\).

- Sides of \(ABCD\) are of the equal length, i.e. \(AB = BC\).

- The rhombus is non–degenerate, i.e. is not a line or a point.

Our conclusion is that \(AC \bot BD\). To prove this theorem, first we need to transform the above conditions and the conclusion into a set of polynomials. How we can achieve this? Let’s focus on the first condition. In general, we are given two lines \(A_1A_2\) and \(B_1B_2\). To express the relation between those two lines, i.e. that \(A_1A_2\) is parallel \(B_1B_2\), we can relate slopes of those lines:

Clearing denominators in the above expression and putting all terms on the left hand side of the equation, we derive a general polynomial describing the first condition. This can be literally translated into Python:

def parallel(A1, A2, B1, B2):

"""Line [A1, A2] is parallel to line [B1, B2]. """

return (A2.y - A1.y)*(B2.x - B1.x) - (B2.y - B1.y)*(A2.x - A1.x)

assuming that A1, A2, B1 and B2 are instances of Point class. In the case of our rhombus, we will take advantage of the fixed coordinate system and simplify the resulting polynomials as much as possible. The same approach can be used to derive polynomial representation of the other conditions and the conclusion. To construct \(\mathcal{H}\) and \(g\) we will use the following functions:

def distance(A1, A2):

"""The squared distance between points A1 and A2. """

return (A2.x - A1.x)**2 + (A2.y - A1.y)**2

def equal(A1, A2, B1, B2):

"""Lines [A1, A2] and [B1, B2] are of the same width. """

return distance(A1, A2) - distance(B1, B2)

def perpendicular(A1, A2, B1, B2):

"""Line [A1, A2] is perpendicular to line [B1, B2]. """

return (A2.x - A1.x)*(B2.x - B1.x) + (A2.y - A1.y)*(B2.y - B1.y)

The non–degeneracy statement requires a few words of comment. Many theorems in geometry are true only in the non–degenerative case and false or undefined otherwise. In our approach to theorem proving in algebraic geometry, we must supply sufficient non–degeneracy conditions manually. In the case of our rhombus this is \(x_B > 0\) and \(y_C > 0\) (we don’t need to take \(x_C\) into account because \(AB = BC\)). At first, this seems to be a show stopper, as Gröbner bases don’t support inequalities. However, we can use Rabinovich’s trick and transform those inequalities into a single polynomial condition by introducing an additional variable, e.g. \(a\), about which we will assume that is positive. This gives us a non–degeneracy condition \(x_B y_C - a\).

With all this knowledge we are ready to prove the main theorem. First, let’s declare variables:

>>> var('x_B, x_C, y_C, x_D, a')

(x_B, x_C, y_C, x_D, a)

>>> V = _[:-1]

We declared the additional variable \(a\), but we don’t consider it a variable of our problem. Let’s now define the four points \(A\), \(B\), \(C\) and \(D\):

>>> A = Point(0, 0)

>>> B = Point(x_B, 0)

>>> C = Point(x_C, y_C)

>>> D = Point(x_D, y_C)

Using the previously defined functions we can formulate the hypothesis:

>>> h1 = parallel(A, D, B, C)

>>> h2 = equal(A, B, B, C)

>>> h3 = x_B*y_C - a

and compute its Gröbner basis:

>>> G = groebner([f1, h2, h3], *V, order='grlex')

We had to specify the variables of the problem explicitly in groebner(), because otherwise it would treat \(a\) also as a variable, which we don’t want. Now we can verify the theorem:

>>> reduced(perpendicular(A, C, B, D), G, *V, order='grlex')[1]

0

The remainder vanished, which proves that \(AC \bot BD\). Although, the theorem we described and proved here is a simple one, one can handle much more advanced problems as well using Gröbner bases techniques. One should refer to Franz Winkler’s papers for more advanced examples.