Applications of Gröbner bases¶

The Gröbner bases method is an attractive tool in computer algebra and symbolic mathematics because it is relatively simple to understand and it can be applied to a wide variety of problems in mathematics and engineering.

Let’s consider a set \(F\) of multivariate polynomial equations over a field:

A Gröbner basis \(G\) of \(F\) with respect to a fixed ordering of monomials is another set of polynomial equations with certain nice properties that depend on the choice of the order of monomials and variables. \(G\) will be structurally different from \(F\), but has exactly the same set of solutions.

The Gröbner bases theory tells us that:

- problems that are difficult to solve using \(F\) are easier to solve using \(G\)

- there exists an algorithm for computing \(G\) for arbitrary \(F\)

We will take advantage of this and in the following subsections we will solve two interesting problems in graph theory and algebraic geometry by formulating those problems as systems of polynomial equations, computing Gröbner bases, and reading solutions from them.

Vertex \(k\)–coloring of graphs¶

Given a graph \(\mathcal{G}(V, E)\), where \(V\) is the set of vertices and \(E\) is the set of edges of \(\mathcal{G}\), and a positive integer \(k\), we ask if it is possible to assign a color to every vertex from \(V\), such that adjacent vertices have different colors assigned. Moreover, if graph \(\mathcal{G}\) is \(k\)–colorable, we would like to enumerate all possible \(k\)–colorings this graph.

We will solve this problem using the Gröbner bases method. First of all, we have to transform this graph–theoretical definition of \(k\)–coloring problem into a form that is understandable by the Gröbner bases machinery. This means we have to construct a system of polynomial equations that embeds the structure of a graph and constraints related to the \(k\)–coloring problem.

We start by assigning a variable to each vertex. Given that \(\mathcal{G}\) has \(n\) vertices, i.e. \(|V| = n\), then we will introduce variables \(x_1, \ldots, x_n\). Next we will write a set of equations describing the fact that we allow assignment of one of \(k\) possible colors to each vertex. The best approach currently known is to map colors to the \(k\)–th roots of unity, which are the solutions to the equation \(x^k - 1 = 0\).

Let \(\zeta = \exp(\frac{2\pi\mathrm{i}}{k})\) be a \(k\)–th root of unity. We map the colors \(1, \ldots, k\) to \(1, \zeta, \ldots, \zeta^{k-1}\). Then the statement that every vertex has to be assigned one of \(k\) colors is equivalent to writing the following set of polynomial equations:

We also require that two adjacent vertices \(x_i\) and \(x_j\) are assigned different colors. From the previous discussion we know that \(x_i^k = 1\) and \(x_j^k = 1\), so \(x_i^k = x_j^k\) or, equivalently, \(x_i^k - x_j^k = 0\). By factorization we obtain that:

where \(f(x_i, x_j)\) is a bivariate polynomial of degree \(k-1\) in both variables. Since we require that \(x_i \not= x_j\) then \(x_i^k - x_j^k\) can vanish only when \(f(x_i, x_j) = 0\). This allows us to write another set of polynomial equations:

Next we combine \(F_k\) and \(F_{\mathcal{G}}\) into one system of equations \(F\). The graph \(\mathcal{G}(V, E)\) is \(k\)-colorable if the Gröbner basis \(G\) of \(F\) is non-trivial, i.e., \(G \not= \{1\}\). If this is not the case, then the graph isn’t \(k\)–colorable. Otherwise the Gröbner basis gives us information about all possible \(k\)–colorings of \(\mathcal{G}\).

Let’s now focus on a particular \(k\)–coloring where \(k = 3\). In this case:

Using SymPy’s built–in multivariate polynomial factorization routine:

>>> var('xi, xj')

(xi, xj)

>>> factor(xi**3 - xj**3)

⎛ 2 2⎞

(xi - xj)⋅⎝xi + xi⋅xj + xj ⎠

we derive the set of equations \(F_{\mathcal{G}}\) describing an admissible \(3\)–coloring of a graph:

At this point it is sufficient to compute the Gröbner basis \(G\) of \(F = F_3 \cup F_{\mathcal{G}}\) to find out if a graph \(\mathcal{G}\) is \(3\)–colorable, or not.

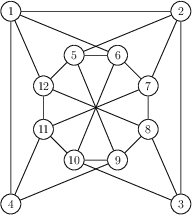

Let’s see how this procedure works for a particular graph:

The graph \(\mathcal{G}(V, E)\).

\(\mathcal{G}(V, E)\) has 12 vertices and 23 edges. We ask if the graph is \(3\)–colorable. Let’s first encode \(V\) and \(E\) using Python’s built–in data structures:

>>> V = range(1, 12+1)

>>> E = [(1,2),(2,3),(1,4),(1,6),(1,12),(2,5),(2,7),(3,8),

... (3,10),(4,11),(4,9),(5,6),(6,7),(7,8),(8,9),(9,10),

... (10,11),(11,12),(5,12),(5,9),(6,10),(7,11),(8,12)]

We encoded the set of vertices as a list of consecutive integers and the set of edges as a list of tuples of adjacent vertex indices. Next we will transform the graph into an algebraic form by mapping vertices to variables and tuples of indices in tuples of variables:

>>> V = [ var('x%d' % i) for i in V ]

>>> E = [ (V[i-1], V[j-1]) for i, j in E ]

As the last step of this construction we write equations for \(F_3\) and \(F_{\mathcal{G}}\):

>>> F3 = [ xi**3 - 1 for xi in V ]

>>> Fg = [ xi**2 + xi*xj + xj**2 for xi, xj in E ]

Everything is set following the theoretical introduction, so now we can compute the Gröbner basis of \(F_3 \cup F_{\mathcal{G}}\) with respect to lexicographic ordering of terms:

>>> G = groebner(F3 + Fg, *V, order='lex')

We know that if the constructed system of polynomial equations has a solution then \(G\) should be non–trivial, which can be easily verified:

>>> G != [1]

True

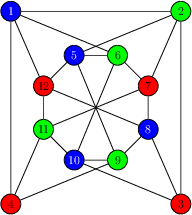

The answer is that the graph \(\mathcal{G}\) is \(3\)–colorable. A sample coloring is shown on the following figure:

A sample \(3\)–coloring of the graph \(\mathcal{G}(V, E)\).

Suppose we add an edge between vertices \(i = 3\) and \(j = 4\). Is the new graph still \(3\)–colorable? To check this it is sufficient to construct \(F_{\mathcal{G'}}\) by extending \(F_{\mathcal{G}}\) with \(x_3^2 + x_3 x_4 + x_4^2\) and recomputing the Gröbner basis:

>>> groebner(F3 + Fg + [x3**2 + x3*x4 + x4**2], *V, order='lex')

[1]

We got the trivial Gröbner basis as the result, so the graph \(\mathcal{G'}\) isn’t \(3\)–colorable. We could continue this discussion and ask, for example, if the original graph \(\mathcal{G}\) can be colored with only two colors. To achieve this, we would have to construct \(F_2\) and \(F_{\mathcal{G}}\) and recompute the basis.

Let’s return to the original graph. We already know that it is \(3\)–colorable, but now we would like to enumerate all colorings. We will start from revising properties of roots of unity. Let’s construct the \(k\)–th root of unity, where \(k = 3\), in algebraic number form:

>>> zeta = exp(2*pi*I/3).expand(complex=True)

>>> zeta

⎽⎽⎽

1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ

- ─ + ───────

2 2

Altogether we consider three roots of unity in this example:

>>> zeta**0

1

>>> zeta**1

⎽⎽⎽

1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ

- ─ + ───────

2 2

>>> expand(zeta**2)

⎽⎽⎽

1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ

- ─ - ───────

2 2

Just to be extra cautious, let’s check if \(\zeta^3\) gives \(1\):

>>> expand(zeta**3)

1

Alternatively, we could obtain all \(k\)–th roots of unity by factorization of \(x^3 - 1\) over an algebraic number field or by computing its roots via radicals:

>>> factor(x**3 - 1, extension=zeta)

⎛ ⎽⎽⎽ ⎞ ⎛ ⎽⎽⎽ ⎞

⎜ 1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ⎟ ⎜ 1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ⎟

(x - 1)⋅⎜x + ─ - ───────⎟⋅⎜x + ─ + ───────⎟

⎝ 2 2 ⎠ ⎝ 2 2 ⎠

>>> roots(x**3 - 1, multiple=True)

⎡ ⎽⎽⎽ ⎽⎽⎽ ⎤

⎢ 1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ 1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ⎥

⎢1, - ─ - ───────, - ─ + ───────⎥

⎣ 2 2 2 2 ⎦

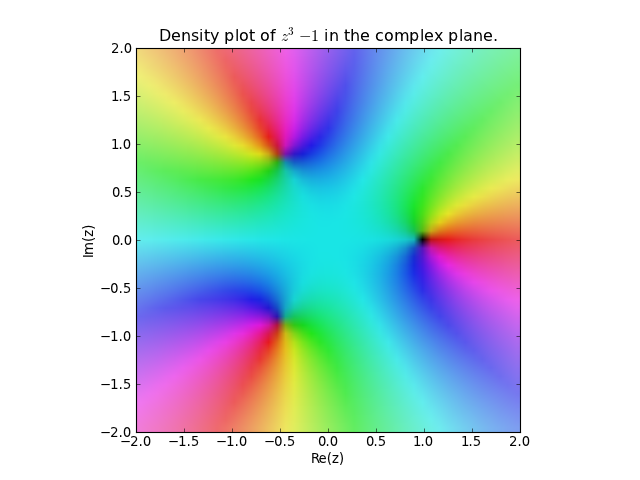

We can visualize roots of \(x^3 - 1\) with a little help from mpmath and matplotlib:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sympy.mpmath import cplot

fig = plt.figure()

axes = fig.add_subplot(111)

axes.set_title(r"Density plot of $z^3 - 1$ in the complex plane.")

cplot(lambda z: z**3 - 1, re=[-2, 2], im=[-2, 2], axes=axes)

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Going one step ahead, let’s declare three variables which will nicely represent colors in the \(3\)–coloring problem and let’s put together, in an arbitrary but fixed order, those variables and the previously computed roots of unity:

>>> var('red,green,blue')

(red, green, blue)

>>> colors = zip(__, _)

>>> colors

⎡ ⎛ ⎽⎽⎽ ⎞ ⎛ ⎽⎽⎽ ⎞⎤

⎢ ⎜ 1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ ⎟ ⎜ 1 ╲╱ 3 ⋅ⅈ ⎟⎥

⎢(1, red), ⎜- ─ - ───────, green⎟, ⎜- ─ + ───────, blue⎟⎥

⎣ ⎝ 2 2 ⎠ ⎝ 2 2 ⎠⎦

This gives as a mapping between algebra of \(3\)–coloring problem and a nice visual representation, which we will take advantage of later.

Let’s look at \(G\):

>>> key = lambda f: (degree(f), len(f.args))

>>> groups = sorted(sift(G, key).items(), reverse=True)

>>> for _, group in groups:

... pprint(group)

...

⎡ 3 ⎤

⎣x₁₂ - 1⎦

⎡ 2 2⎤

⎣x₁₁ + x₁₁⋅x₁₂ + x₁₂ ⎦

[x₁ + x₁₁ + x₁₂, x₁₁ + x₁₂ + x₅, x₁₁ + x₁₂ + x₈, x₁₀ + x₁₁ + x₁₂]

[-x₁₁ + x₂, -x₁₂ + x₃, -x₁₂ + x₄, -x₁₁ + x₆, -x₁₂ + x₇, -x₁₁ + x₉]

Here we split the basis into four groups with respect to the total degree and length of polynomials. Treating all those polynomials as equations of the form \(f = 0\), we can solve them one–by–one, to obtain all colorings of \(\mathcal{G}\).

From the previous discussion we know that \(x_{12}^3 - 1 = 0\) has three solutions in terms of roots of unity:

>>> f = x12**3 - 1

>>> f.subs(x12, zeta**0).expand()

0

>>> f.subs(x12, zeta**1).expand()

0

>>> f.subs(x12, zeta**2).expand()

0

This also tells us that \(x_{12}\) can have any of the three colors assigned. Next, the equation \(x_{11}^2 + x_{11} x_{12} + x_{12}^2 = 0\) relates colors of \(x_{11}\) and \(x_{12}\), and vanishes only when \(x_{11} \not= x_{12}\):

>>> f = x11**2 + x11*x12 + x12**2

>>> f.subs({x11: zeta**0, x12: zeta**1}).expand()

0

>>> f.subs({x11: zeta**0, x12: zeta**2}).expand()

0

>>> f.subs({x11: zeta**1, x12: zeta**2}).expand()

0

but:

>>> f.subs({x11: zeta**0, x12: zeta**0}).expand() == 0

False

>>> f.subs({x11: zeta**1, x12: zeta**1}).expand() == 0

False

>>> f.subs({x11: zeta**2, x12: zeta**2}).expand() == 0

False

This means that, when \(x_{12}\) is assigned a color, there are two possible color assignments to \(x_{11}\). Equations in the third group vanish only when all three vertices of that particular equation have different colors assigned. This follows from the fact that the sum of roots of unity vanishes:

>>> expand(zeta**0 + zeta**1 + zeta**2)

0

but (for example):

>>> expand(zeta**1 + zeta**1 + zeta**2) == 0

False

Finally, equations in the last group are trivial and vanish when vertices of each particular equation have the same color assigned. This gives us \(3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 \cdot 1 = 6\) combinations of color assignments, i.e. there are six solutions to \(3\)–coloring problem of graph \(\mathcal{G}\).

Based on this analysis it is straightforward to enumerate all six color assignments, however we can make this process fully automatic. Let’s solve the Gröbner basis \(G\):

>>> colorings = solve(G, *V)

>>> len(colorings)

6

This confirms that there are six solutions. At this point we could simply print the computed solutions to see what are the admissible \(3\)–colorings. This is, however, not a good idea, because we use algebraic numbers (roots of unity) for representing colors and solve() returned solutions in terms of those algebraic numbers, possibly even in a non–simplified form.

To overcome this difficulty we will use previously defined mapping between roots of unity and literal colors and substitute symbols for numbers:

>>> for coloring in colorings:

... print [ color.expand(complex=True).subs(colors) for color in coloring ]

...

[blue, green, red, red, blue, green, red, blue, green, blue, green, red]

[green, blue, red, red, green, blue, red, green, blue, green, blue, red]

[green, red, blue, blue, green, red, blue, green, red, green, red, blue]

[blue, red, green, green, blue, red, green, blue, red, blue, red, green]

[red, blue, green, green, red, blue, green, red, blue, red, blue, green]

[red, green, blue, blue, red, green, blue, red, green, red, green, blue]

This is the result we were looking for, but a few words of explanation are needed. solve() may return unsimplified results so we may need to simplify any algebraic numbers that don’t match structurally the precomputed roots of unity. Taking advantage of the domain of computation, we use the complex expansion algorithm for this purpose (expand(complex=True)). Once we have the solutions in this canonical form, to get this nice visual form with literal colors it is sufficient to substitute color variables for roots of unity.

Tasks¶

Instead of computing Gröbner basis of \(F\), simply solve it using solve(). Can you enumerate color assignments this way? If so, why?

(solution)

Use this procedure to check if:

- the graph with 12 vertices and 23 edges is \(2\)–colorable.

- the graph with 12 vertices and 24 edges is \(4\)–colorable.

(solution)